2,800,000 Years Old Fossils in Ethiopia May Be a New Human Specie

Earliest Human Species Possibly Found in Ethiopia

by Charles Q. Choi

An ancient jawbone fragment is the oldest human fossil discovered yet, a bone potentially from a new species that reveals the human family may have arose a half million years earlier than previously thought, researchers say.

This find also sheds light on the kind of landscape where humans first originated, scientists added.

Although modern humans are the only human lineage alive today, other human species once roamed the Earth. These extinct lineages were members of the genus Homo just as modern humans are.

A close-up of the LD 350-1 mandible unearthed from the Ledi-Geraru research area. Scientists found the mandible combines a mix of primitive traits seen in the more apelike Australopithecus species and traits found in more human early Homo species. The new finding is detailed online today (March 4) in the journal Science. (Photo credit: William Kimbel)

For decades, scientists have been searching Africa for signs of the earliest phases of the human family, during the shift from more apelike Australopithecus species to more human early Homo species. Until now, the earliest credible fossil evidence of the genus Homo was dated to about 2.3 million or 2.4 million years ago.

Now researchers have found a human fossil in Ethiopia about 2.8 million years old. The scientists detail their findings in two papers online today (March 4) in the journal Science.

“There is a big gap in the fossil record between about 2.5 million and 3 million years ago — there’s virtually nothing relating to the ancestors of Homo from that time period, in spite of a lot of people looking,” research team co-leader and study co-author Brian Villmoare, a paleoanthropologist at the University of Nevada in Las Vegas,told Live Science. “Now we have a fossil of Homo from this time, the earliest evidence of Homo yet.

New human species?

The fossil was found by team member Chalachew Seyoum in 2013 at the Ledi-Geraru research area in the Afar region of Ethiopia. “One hill was particularly rich in fossils — it was probably a bend in a stream, where bones tended to gather after animals died,” Villmoare said. “We found this fossil coming out of that hill.”

Another close-up view of the Homo mandible, shown just steps from where Arizona State University graduate student Chalachew Seyoum from Ethiopia spotted it. The scientists involved in the discovery aren’t sure if the fossil belongs to a new species or to a known, extinct human species, such as Homo habilis. They plan to learn more about the fossil before making that decision and giving it a name. (Photo credit: Kaye Reed)

The fossil, known as LD 350-1, preserves the left side of the lower jaw along with five teeth. “Once we found it, we knew immediately what it was — we could tell it was a human ancestor,” Villmoare said. “We were jumping up and down the side of that hill.”

The scientists dated the fossil by analyzing the layers of volcanic ash above and below it. “When volcanoes erupt, they send out a layer of ash that contains radioactive isotopes, and these isotopes start going through radioactive decay,” Villmoare said. “We can use this to figure out how old those layers of ash are.”

The fossil was found near the Ethiopian site of Hadar, home to Australopithecus afarensis, the ancient species that included “Lucy” that was long thought to be a potential ancestor of the human family. Moreover, LD 350-1 only dates to about 200,000 years after Lucy, and its primitive sloping chin resembles that of Australopithecus. However, the fossil’s teeth and even proportions of its jaw suggest it belonged to the genus Homo rather than Australopithecus.

“It’s a mixture of more primitive traits from Australopithecus with quite a few traits only seen in later Homo,” Villmoare said.

The scientists do not yet know whether this fossil belongs to a new species or to a known, extinct human species such as Homo habilis, Villmoare said.

“We are holding back on that — we are hoping to find more of it, learn more about what it looked like, before we give the species a name,” Villmoare said.

Where Homo evolved

The geological setting in which the fossil was discovered suggests the site was probably similar to African locations like the Serengeti Plains or the Kalahari back when this specimen was alive — mostly a mix of grasslands and shrubs, with scatterings of trees near water, the researchers say. There was also a lake and rivers in the area with hippos, antelope, elephants, crocodiles and fish, they added.

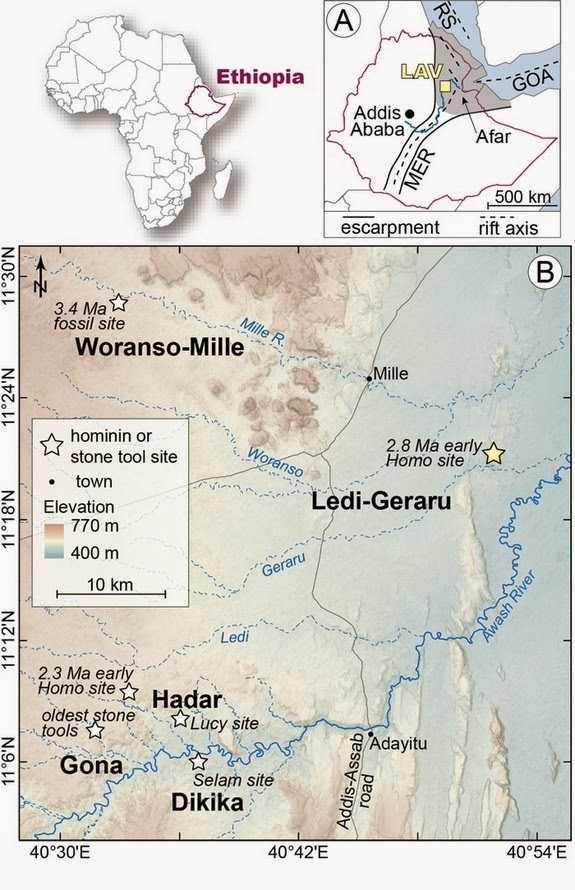

A detailed map of the location of the Ledi-Geraru site, where the Homo mandible was discovered, in reference to other important fossil sites in Ethiopia. (Image Credit: Erin DiMaggio)

“This find helps place the evolution of Homo geographically and temporally — it tells us where and when Homo evolved,” Villmoare said.

Prior research suggests that global climate change intensified about 2.8 million years ago, resulting in increasing African aridity that spurred evolutionary changes in many mammal lineages, potentially including the origin of Homo.

“We can see the 2.8 million-year-old aridity signal in the Ledi-Geraru faunal community,” research team co-leader and study co-author Kaye Reed of Arizona State Universitysaid in a statement. “But it’s still too soon to say that this means climate change is responsible for the origin of Homo. We need a larger sample of hominin fossils and that’s why we continue to come to the Ledi-Geraru area to search.”

There’s a chance the mandible belonged to an individual of the species Homo habilis, as a report also out today (March 4) suggests a key fossil of that species also is a mix of both primitive and more advanced traits. Shown here, a partial lower jaw, bones of the braincase and hand bones from a Homo habilis called the Olduvai Hominid 7 (OH 7). (Photo credit: John Reader)

Another report announced today (March 4) suggests that a key fossil of Homo habilis, which until now was the oldest known member of Homo, is an unexpected mix of primitive and advanced traits. This makes it a good match for the new LD 350-1 fossil, the researchers say.

“These findings raise more questions than they answer,” Villmoare said. “Hopefully these questions will be answered by further fieldwork.”

Source:

Original people

Africason

Africason is a die-hard believer in Africa.

Facebook: facebook.com/AfricanSchool

Comments

Post a Comment